I.

It wouldn’t be particularly surprising if we cure obesity soon. If anything, it’s old news that we’re close to curing obesity! You’ve likely already heard about Semaglutide, the drug that is so effective that it single-handedly prevented Denmark from falling into a recession (Novo Nordisk, the company that produces Semaglutide, is Danish). The idea is pretty simple: you give a ton of money to Novo Nordisk, you take the drug, you stop eating so much, and you lose weight. Done.

What should we cure next? Alcoholism seems like a good choice. The data on how many alcoholics there are in the UK is a bit all over the place, but it seems like the number of alcoholics is somewhere between 1% and 20% of the adult population, depending on whether you’re looking at people who drink way too much or people who drink waaaaaay too much. In 2021, there were about 21,000 alcohol-related deaths in the UK (compared to around 76,000 from smoking). GiveWell also estimates that alcohol consumption is responsible for 2 million deaths per year in Low and Middle income countries, which is obviously a lot.

People who drink too much alcohol also do lots of things that are just very, very dumb. They drive cars and kill people, they’re violent (alcohol is thought to play a part in half of all violent crime in the UK), they fall over and hurt themselves (about 10% of visits to the emergency department in the UK are alcohol-related).

It would be good if there were fewer alcoholics. So, why not cure alcoholism?

(I should pause here to mention that I don’t really have a view on whether alcoholism is a “disease”, as the Alcoholics Anonymous people like to insist, or a strong preference for alcohol, or a moral failing, or a useful sign someone will be a good hang, or whatever else. It doesn’t much matter for the purposes of this article, so if you don’t like the ‘cure/disease’ terminology, substitute it with your preferred way of talking about people who drink a lot of alcohol.)

Unsurprisingly, we have tried to cure alcoholism. We’ve tried a lot of different things, actually: Alcoholics Anonymous and similar programs, CBT for alcoholism, something called ‘Motivational Enhancement Therapy’ (which I must say sounds dreadful), mindfulness meditation for alcoholism, and a load of other things of varied effectiveness. But what I’m especially interested in are the Semaglutide-like solutions for alcoholism: drugs that make you stop wanting to drink alcohol.

There are a few candidates here. Naltrexone is the major one, and it works by blocking opioid receptors. But wait, wouldn’t that make it a drug for people addicted to opioids, rather than alcoholics? Yes, and in fact it was originally developed to help opioid addicts! But it’s also prescribed to help alcoholics, because it reduces the dopamine release from the brain after drinking alcohol, which makes getting drunk much less enjoyable. Nalmefene is a very similar drug that does basically the same thing.

Disulfiram, often called Antabuse, works differently. The trick here is that it makes drinking alcohol so horrible that you don’t want to do it. Here’s an experience from someone on Reddit:

I sincerely hope anybody didn't/doesn't perform the experiment that I did a few hours ago. I read the side-effects of drinking on disulfiram, have been taking 250mg daily for just 5 days, and figured what the hell let's roll those dice.

I figured, given the short period I've been taking it, I'd experience flushing and a minor headache, possibly some dizziness. Nothing that the fact that I'd be buzzed couldn't overcome.

I was WRONG SO WRONG NEVER BEEN MORE WRONG. I've had withdrawal symptoms that landed me in the ICU more than once, and I can now say first-hand, buddy if you fuck with disulfiram you will be sorry. The intensity of the reaction to half a beer had nothing on my ICU visits. It started with an abnormal light-headed feeling that I wasn't expecting, given the amount of alcohol I'd imbibed. Then came the headache. I haven't experienced anything close to this in my life and my blood pressure has been 210/140 during detox and withdrawal, well within stroke range, easily should've caused the worst headache of my life.

Pounding, throbbing, can't think about anything else, "Holy shit I'm so sorry, I'll never do this again, please make this stop!" absolutely awful turn an atheist into a believer in Satan level of badness.

You get the idea. And finally, there’s Acamprosate, which is a bit of a confusing one. As far as I can tell, it doesn’t actually really help you give up drinking at all. Instead, it helps you stay off the drink once you’ve already quit by reducing withdrawal symptoms and post-acute withdrawal symptoms (a sort of withdrawal aftershock that persists for months after actually giving up drinking). But I’m not sure if this description is exactly right. Some people on Reddit mention that it’s really useful in combating cravings, which I’m not sure is exactly the same thing as reducing withdrawal symptoms - or maybe it is? Either way, it’s commonly prescribed to alcoholics, so its efficacy is still worth examining.

There are other drugs that are prescribed off-label for alcoholics: Baclofen, Topiramate, Varenicline, and probably more still. But let’s start with the ones that doctors actually prescribe for Alcohol use disorder - how effective are they?

II.

Here’s a (possibly?) surprising fact: most (around 78%) of the alcoholics who successfully stop drinking do so without any sort of treatment. Now, this fact alone doesn’t really say much about how useful treatment is, and DEFINITELY DOES NOT IMPLY THAT IT’S EASIER TO QUIT WITHOUT TREATMENT.

For example, imagine it were the case that 99.9% of alcoholics who attempt to stop drinking do so without treatment, but this only applied to 78% of successful giver-uppers. You can see that the question we really care about here is whether the successful abstainers are disproportionately those who got treatment, not about the absolute percentage of them who got treatment.

But still, it does seem both like quite a lot of alcoholics who successfully give up do so without treatment, and also that quite a lot of people who try to give up alcohol without treatment are in fact successful - the number seems to be around a 45% success rate without any treatment at all. We should have this in mind when we look at how effective the medications are - if they have a 45% success rate (or lower!), they’re probably basically useless.

(There are some reasons this may not always be the case. If people who have especially severe alcoholism are more likely to be prescribed medication, and those people are also much less likely to succeed giving up alcohol without treatment, we might find that the drug has a success rate that’s much lower than 45% while also being higher than the success rate in the control group.)

Do the drugs work? Maisel et al. (2013) conduct a meta-analysis that includes 64 placebo-controlled Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) focusing either on Naltrexone (the one that blocks opioid receptors) or Acamprosate (the one that reduces withdrawal symptoms). Across a load of outcomes, they find that the aggregated effect size of Naltrexone and Acamprosate is a hedges’ g of 0.2091. What the hell does that mean? Good question.

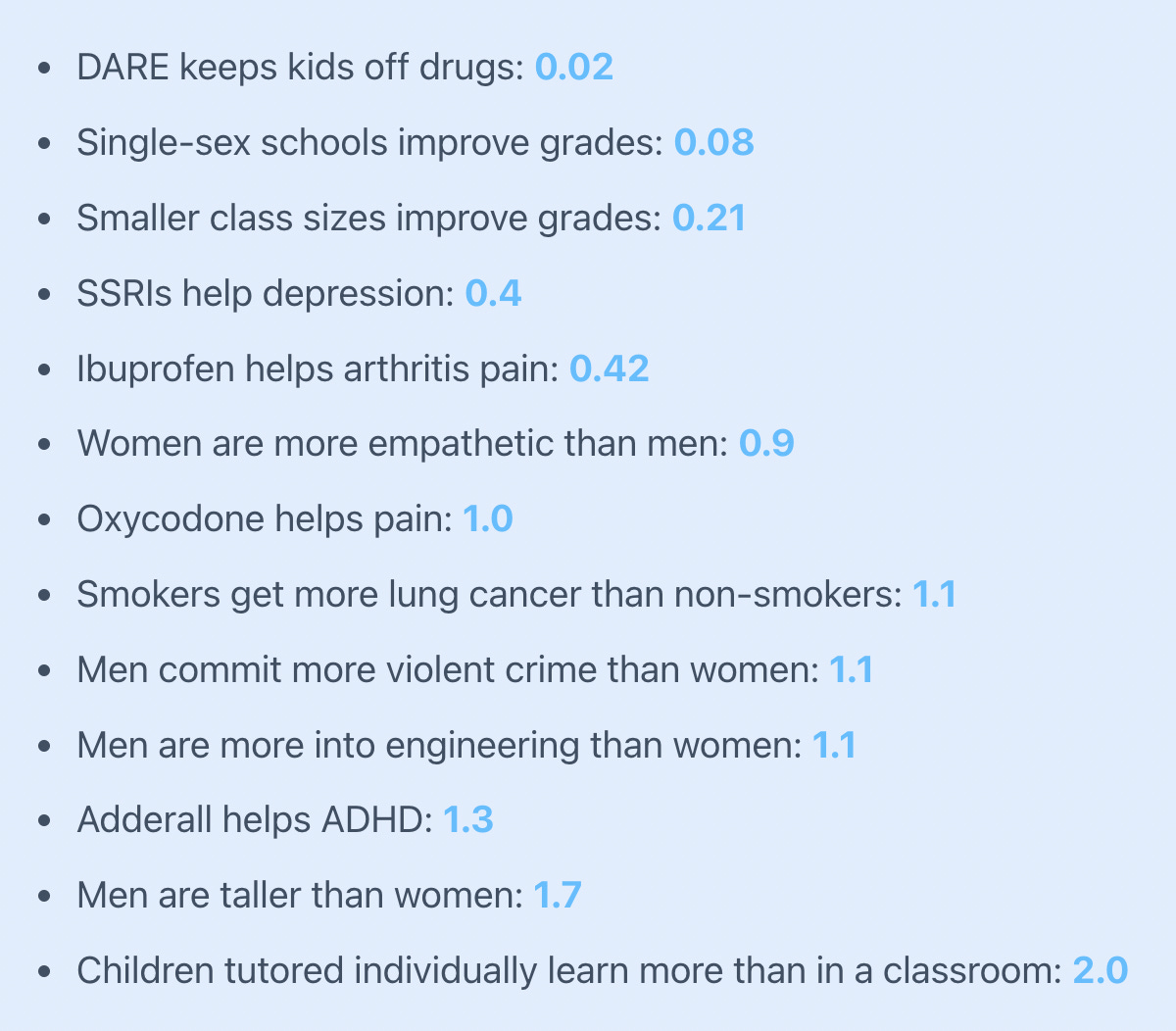

The standard explanation is that a hedges’ g of between 0.2 and 0.5 is a “small” effect size. But how small is small? Scott Alexander has a useful post that gives some examples of the effect sizes of various interventions, as can be seen below.

So when we say a small effect size in this context, you can think ‘much more effective than DARE is at getting kids off drugs, but much less effective than Adderall is for ADHD’. Slightly disappointing, really.

Another way to think about it, as the authors of the study point out, is that you would need to treat 9 people with Naltrexone to prevent one additional case of ‘return to heavy drinking’ or 8 people with Acamprosate to achieve one additional case of abstinence. Sadly, these drugs aren’t like Semaglutide, where the average person taking the drug can expect to lose 9.9% of their body weight after 20 weeks, compared to 0.4% of body weight lost for those on the placebo.

Okay, what about Antabuse? That’s the one that just makes drinking alcohol really, really awful. For this one, I have good news and bad news. The good news is that a meta-analysis found that the aggregated effect size of Antabuse on a range of outcomes was a hedges’ g of 0.58. As a reminder, that’s a ‘moderate’ effect size that implies it’s more effective than Ibuprofen is for arthritis pain. The bad news is that the effect disappears entirely when only looking at blinded RCTs.

(Just as a quick reminder: double-blind/blinded RCTs mean that neither the patient nor the doctor knows who is getting the treatment and who is getting the placebo. Open-label RCTs mean that both the doctor and the patient know who is receiving the treatment and who is receiving the placebo.)

The authors of the paper claim this is to be expected. After all, Antabuse partially works because you know you’re getting the real thing and that disincentivises you from drinking. If you might just be getting a placebo, what reason is there not to drink? They write:

The drug’s effectiveness depends directly upon the patient’s anticipations. Because the action on potential drinking behavior depends upon a thought process, disulfiram can be considered a pharmacologically assisted psychotherapy. Because of this similarity to psychotherapy, and because psychotherapy studies are necessarily open, only open-label studies could show efficacy in disulfiram RCTs.

Which is… kinda suspicious? Psychotherapy is necessarily “open-label” because obviously someone getting actual psychotherapy is going to know that they’re getting psychotherapy rather than being on a waiting list (which is commonly used as a control). This doesn’t really imply that a study that tests a medication that is similar in some ways to psychotherapy has to be open-label to be effective.

And given that most of these trials went on for at least 12 weeks, you’d sort of expect an actual drug that made drinking alcohol extremely unpleasant to have some sort of effect here, even if they didn’t know with certainty in advance that they weren’t getting a placebo. The only explanation that works here is that people were so scared of the negative effect of Antabuse that even those on the placebo decided to abstain from alcohol entirely.

In fact, this is so weird that it makes me think I’ve misunderstood something. The drug doesn’t seem to be effective at all when the RCTs are blinded, and the study authors just shrug their shoulders and say this is to be expected? What?!

Mark me down as a bit suspicious that these results are really as good as they appear when the aggregate effect size (that includes both blinded and open-label RCTs) is given. One paper actually did both a blinded RCT and an open-label RCT to see what would happen. The meta-analysis authors write:

In the blind portion, as could be expected, no significant difference between disulfiram and the control groups was found. But surprisingly, even in the open-label portion comparing disulfiram to no disulfiram, there were no differences between the groups.

Yes, weird indeed.

III.

Okay, so I’m not particularly impressed by these drugs that are supposed to be very useful for giving alcohol. For Naltrexone and Acamprosate, the effect appears to be real but small. For Antabuse, I’m suspicious. The effect size if you exclude the blinded studies is actually pretty impressive (hedges’ g = 0.7). The blinded studies have no significant effect, so the authors of the meta-analysis just aggregate these all into a moderate effect size of 0.58. I’m not sure what to think here, but let’s just say I wouldn’t be too optimistic about these drugs if I were a serious alcoholic.

Does anything else work? Alcoholics Anonymous? CBT? Other therapies? I think the general answer is… kinda, but not really. Like with the drugs, the effect sizes involved are small. The chance of you recovering from alcoholism is fairly significant if you just try to give up, and these other options seem like they increase your chances a little bit, but not much. Scott Alexander did a piece on this (it seems like half the time I write a piece I get to a point where I realise Scott did something similar first!) and writes:

All treatments for alcoholism, including Alcoholics Anonymous, psychotherapy, and just a few minutes with a doctor explaining why she thinks you need to quit, increase this already-high chance of recovery a small but nonzero amount. Furthermore, they are equally effective after only a tiny dose: your first couple of meetings, your first therapy session. Some studies suggest that inpatient treatment with outpatient followup may be better than outpatient treatment alone, but other studies contradict this and I am not confident in the assumption.

It sounds odd, but the best advice to someone who is an alcoholic is probably: just try to give up, you’ve got a pretty good chance of succeeding. It sounds a bit shit, doesn’t it? I once made the case that good advice should be non-obvious, and the advice ‘you should just try to stop drinking, have you thought of that?’ fails the non-obvious test. So what about: try to give up drinking, take some Antabuse if you can get it because there’s a chance it’s actually pretty effective, and go to Alcoholics Anonymous too just for good measure.

There do seem to be some differences in which outcomes the different drugs affect. Naltrexone seems to be better at reducing the number of days that someone does a lot of drinking, as well as reducing cravings for alcohol. Acamprosate, on the other hand, seems to be more likely to result in complete abstinence from alcohol.

Excellent analysis. I wanted to comment on some of these studies that show, for example, 45% of alcoholics can quit without treatment. I'm a recovered alcoholic, and spent a lot of time talking about these types of studies in rehab with the counsellors. They are endlessly annoyed by the very simple errors made, which make these studies extremely misleading.

Every single person in AA (aside from a few who were court-ordered) are there because they have already tried abstinence and failed. They've likely tried it dozens of times on their own. Those trying various medications have also attempted abstinence and failed. This should be pretty obvious; You only go to your doctor or a meeting once you've accepted that you can't fix it on your own.

But what these studies do is take a group of people and they find that abstinence works for 45% of them. That's great! But the second group of people in treatment who are being compared have already self selected out of this 45%. This second group of people has a 0% success rate with abstinence.

So if a program works more than 0% of the time, it's better than abstinence! Because we already know abstinence worked 0% of the time for these people.

Sadly, there are essentially no studies that properly compare abstinence with treatment. Remember when people tried to study porn usage in men, but found it very hard because they couldn't find men who had never watched porn? There's a similar issue here. You can't find alcoholics ready to go through treatment who haven't already tried and failed with abstinence.

And maybe an unpopular opinion: If you can just decide one day give to up alcohol, and successfully do so.... were you really an alcoholic? Is that who we care about here? Many people struggle for decades trying to quit. They lose all their friends and family and job along the way. It's pretty silly to treat these people similarly.

On the Antabuse not showing a significant effect in blinded studies, you write: "The only explanation that works here is that people were so scared of the negative effect of Antabuse that even those on the placebo decided to abstain from alcohol entirely."

I would guess this is exactly what's happening. I don't know any of this for sure, but I would guess that a lot of the effectiveness from Antabuse comes from people not even trying to have a drink because they don't want the misery, rather than trying to have a drink and experiencing the misery first-hand. So if much of the effectiveness is just coming from that anticipation, it really won't matter whether you're given a placebo if you think there's a decent chance of it being the real thing.